Introduction

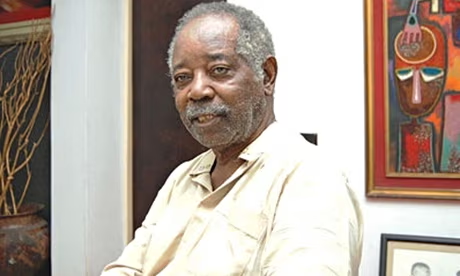

Jacob Festus Adeniyi Ajayi, commonly known as J.F. Ade Ajayi (May 26, 1929 – August 9, 2014), was a Nigerian historian, educator, and intellectual titan whose work reshaped the study of African history. As a leading figure of the Ibadan School of History, Ajayi championed African perspectives, emphasizing internal forces and historical continuity over Eurocentric narratives. His seminal works, including Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841–1891 and A Thousand Years of West African History, decolonized African historiography, earning him global acclaim. A former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos and recipient of Nigeria’s highest honor, the Nigerian National Merit Award, Ajayi’s rigorous scholarship and commitment to nation-building left an indelible mark on Nigeria and African studies.

Early Life and Education

Born in Ikole-Ekiti, Ekiti State, to Christian parents, Ezekiel Adeniyi Ajayi, a postmaster and secretary to the local ruler, and Comfort Bolajoko, Ajayi grew up in a disciplined household that valued education. He attended Ekiti Central School (now Christ’s School, Ado-Ekiti) before securing a scholarship from the Ikole-Ekiti Native Authority to study at Igbobi College, Lagos (1940–1946). His academic prowess led to a year at Yaba Higher College, Lagos, and admission to University College, Ibadan (UCI), in 1948, where he earned a BA in History, Latin, and Classics in 1951. Awarded a Nigerian government scholarship, Ajayi pursued an honors degree in History at the University of Leicester (1952–1955), graduating with first-class honors under Professor Jack Simmons, who “made a historian out of him.” He completed his PhD at the University of London (1958), focusing on Christian missions in Nigeria, supervised by Professor G.S. Graham. In 1956, he married Christie Martins, with whom he had five children.

Academic Career and the Ibadan School

Ajayi joined the University of Ibadan in 1958 as a lecturer, rising to professor in 1963 and becoming a central figure in the Ibadan School of History alongside Kenneth Dike and S.O. Biobaku. This group challenged colonial historiography, which dismissed African history as insignificant, by emphasizing African agency and intra-African relations. Ajayi’s Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841–1891: The Making of a New Elite (1965) demonstrated how missionary education created a Western-educated African elite, fostering early nationalism, as explored in his 1960 Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria paper. His co-edited A Thousand Years of West African History (1965) with Ian Espie used archaeological and Arabic texts to counter Eurocentric narratives, remaining a staple in African education.

Ajayi’s methodology prioritized historical continuity over disruptive events, viewing colonialism as a “mere episode” in Africa’s long history, a controversial stance that underscored lasting African resilience. His use of oral sources, particularly in pre-20th-century Yoruba history, balanced with written records, uncovered nuanced truths about events like the British colonization of Lagos. His dispassionate style, evident in his critical yet measured appraisal of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, a personal hero, set a new standard for African historiography. As general editor of the Ibadan History Series, he published works like History of West Africa (1971, 1974) and Groundwork of Nigerian History (1980), shaping academic curricula.

Public Service and Educational Reform

As Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos (1972–1978), Ajayi transformed a struggling institution into one of international repute, implementing corruption-proof systems and reorganizing academic structures. He reformed Nigeria’s school curriculum to reflect Afrocentric research, collaborating with policymakers to produce textbooks and a historical events handbook for census-takers, enabling age estimates for non-literate populations (e.g., “born in the year of influenza” as 1918). Outside academia, he advised traditional rulers on post-colonial roles and mediated between state governors, avoiding partisan politics. His 2001 biography, A Patriot to the Core, on Samuel Ajayi Crowther, highlighted the elite’s divergence from traditional rulers, while his 2010 contribution to Slavery and Slave Trade in Nigeria emphasized the overlooked trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean trades.

Global Influence and Nationalism

Ajayi’s scholarship extended globally through roles at the International Africa Institute in London, UNESCO’s General History of Africa (editing Volume VI on the 19th century), and as a visiting professor at UCLA (1963). He saw religious movements like the Fulani Jihad and Christian missions as foundations for Nigerian nationalism, creating educated classes that challenged European rule while adopting Western structures. His nuanced critique of Pan-Africanism as a nationalist base reflected his commitment to grounded, context-specific analysis. His 2004 rebuttal to the Oba of Benin’s claim about Yoruba progenitor Oduduwa, commissioned by the Yoruba Council of Elders, showcased his role as a cultural arbiter.

Recognition and Legacy

Ajayi’s honors include the Nigerian National Merit Award (1986), University of Lagos’s 25th Anniversary Gold Medal (1987), and the Nigerian Centenary Award (2014). He was a Founding Fellow of the Historical Society of Nigeria (1980), Vice President of the Royal African Society, London, and a member of UNESCO’s Advisory Committee. In 2014, his 85th birthday was marked by a 558-page Festschrift, J.F. Ade Ajayi: His Life and Career, and a 233-page Book of Tributes at his funeral in Ikole-Ekiti, where he received a traditional gun salute. Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan eulogized him as “one of Africa’s greatest historians.”

Ajayi’s later years saw a return to his Christian faith, leading a men’s Bible study fellowship from 1996. His 2004 address, “When Salt Has Lost Its Saltiness,” lamented the decline of Nigerian universities and history’s relevance, urging historians to rethink methodologies for nation-building. Posts on X, including @HistoryVille’s 2025 quote, “Our common mortality makes us all brothers,” reflect his enduring influence.

Personal Life and Challenges

Ajayi’s integrity and mild demeanor made him an effective leader, chairing committees with calm authority. Survived by his wife, Chief Christie Ajayi, children, and grandchildren, he remained a private figure, focusing on scholarship. His regret over not writing a full Crowther biography and the decline of Nigerian academia in the 1980s were personal challenges, yet his contributions remain foundational.

Conclusion

J.F. Ade Ajayi’s rigorous scholarship and Afrocentric vision revolutionized African history, restoring agency to its narratives. His leadership in the Ibadan School, educational reforms, and mediation in public life shaped Nigeria’s intellectual and cultural identity. As a historian who saw the past as a tool for nation-building, Ajayi’s works, like Christian Missions and Yoruba Warfare in the Nineteenth Century, remain vital. His legacy, celebrated in Nigeria and globally, inspires historians to illuminate Africa’s past with truth and purpose, ensuring his place as a giant of African historiography.

Sources: The Guardian, Wikipedia, Cambridge Core, ResearchGate, African Studies Association, Dictionary of African Christian Biography.