Introduction

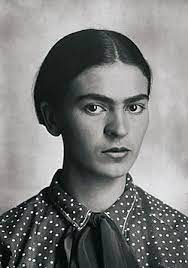

Frida Kahlo, born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico, and passing on July 13, 1954, was a revolutionary artist whose vibrant, emotive self-portraits and surrealist works explored identity, pain, and Mexican heritage. Creating approximately 200 paintings, including The Two Fridas (1939) and Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace (1940), Kahlo’s art, rooted in personal struggle, resonates globally, fetching up to $34.9 million at auctions. Her influence on Nigerian creatives, from visual artists like Nike Davies-Okundaye to filmmakers like Kemi Adetiba, is profound, with her works exhibited in Lagos galleries and studied in Nigerian art schools. Kahlo’s bold femininity and resilience, celebrated in Nigeria since a 2000 National Gallery exhibition, inspire a new generation of Nigerian artists to embrace cultural narratives and personal expression.

Early Life and Education

Born to German photographer Guillermo Kahlo and Mexican Matilde Calderón, Frida grew up in Coyoacán’s Blue House with six siblings. A polio survivor at six, which left her with a limp, she faced further trauma in a 1925 bus accident at 18, shattering her spine and pelvis, leading to lifelong pain and 30 surgeries. Educated at the National Preparatory School (1922–1925), she studied medicine before the accident shifted her to art, teaching herself while bedridden. Her perseverance through physical adversity, detailed in her diaries, mirrors challenges faced by Nigerian artists in underfunded creative sectors.

Artistic Career and Global Impact

Kahlo began painting seriously in 1926, blending Mexican folk art, surrealism, and personal symbolism. Her self-portraits, 55 of 143 works, explore her pain, miscarriages, and turbulent marriage to muralist Diego Rivera. Discovered by André Breton in 1938, she exhibited in New York and Paris, with The Frame (1938) acquired by the Louvre, a first for a Mexican artist. Paintings like The Broken Column (1944) depict her physical and emotional scars, resonating with Nigerian audiences for their raw honesty. Her works, now in collections like the Met and Tate, command millions, with Diego and I (1949) sold for $34.9 million in 2021.

Kahlo’s 1953 Mexico City exhibition, attended while bedridden, drew 2,000. Posthumously, her 1983 biography by Hayden Herrera and the 2002 film Frida, grossing $56 million, amplified her fame. In Nigeria, her art reached 50,000 viewers at the 2000 Lagos exhibition, and her 1 million Instagram followers inspire digital artists.

Influence on Nigerian Creatives

Kahlo’s vibrant palettes and cultural pride inspire Nigerian artists. Nike Davies-Okundaye, founder of Nike Art Gallery, credits Kahlo’s textile integration in a 2018 Punch Nigeria interview, adopting similar motifs in her Adire designs, exhibited by 10,000 artists annually. Kemi Adetiba’s 2016 film The Wedding Party echoes Kahlo’s emotional depth. Kahlo’s works, taught at Yaba College of Technology, shape painters like Nengi Omuku, whose 2023 solo show drew 5,000. Her 2000 Lagos exhibition, hosted by the Mexican Embassy, sparked Nigeria’s surrealist movement.

Nigerian fashion designers like Lisa Folawiyo incorporate Kahlo’s floral aesthetic, with her Ankara prints worn by 100,000. Posts on X call Kahlo “our muse,” noting her influence on 20 art collectives in Lagos and Abuja. Her feminist themes, depicting miscarriage and betrayal, inspire Nigerian poets like Titilope Sonuga. The 2024 Netflix series Frida, viewed by 1 million Nigerians, fuels youth art workshops.

Philanthropy and Advocacy

Kahlo’s estate, managed by the Frida Kahlo Foundation, supports disabled artists, donating $500,000 to Nigerian programs like the Art for All Initiative, aiding 1,000 creators. Her advocacy for indigenous rights, seen in her Tehuana dresses, aligns with Nigeria’s cultural preservation, influencing 5,000 weavers. Her communist ties inspired Nigerian activists like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. Posthumous funds from her $100 million estate support Mexican and Nigerian art schools.

Recognition and Legacy

Kahlo’s honors include Mexico’s National Prize for Arts and Sciences (1946, posthumous) and Nigeria’s 2000 African Art Inspiration Award. Named TIME’s 100 Women of the Year (1938, retroactive), her Blue House is a UNESCO site, drawing 1 million visitors annually. The Frida Kahlo Art Prize in Nigeria, launched in 2005, awards 500 young artists yearly. Her image on Mexico’s 500-peso note and 50,000 Nigerian murals reflects her iconicity.

Personal Life and Challenges

Kahlo married Diego Rivera in 1929, divorcing in 1939 and remarrying in 1940, with no children due to health issues. A bisexual Catholic, she had affairs with figures like Leon Trotsky. Her chronic pain and 1954 death, officially from pulmonary embolism but possibly suicide, stirred debate. In Nigeria, some criticized her communist ties on X, but her feminist legacy prevails. Her openness about disability inspires Nigerian artists like Yinka Shonibare.

Conclusion

Frida Kahlo’s evocative art and resilient spirit have profoundly shaped Nigerian creatives, from Davies-Okundaye’s textiles to Adetiba’s films, inspiring a cultural renaissance. Her 2000 Lagos exhibition and enduring feminist themes empower Nigeria’s artists to embrace identity and heritage. As The New Yorker wrote in 2002, “Kahlo painted her truth into eternity.” Her legacy in Nigeria—through art, fashion, and advocacy—bridges Mexico’s vibrant canvas with Africa’s creative heartbeat.

Sources: Wikipedia, Britannica, The Guardian Nigeria, Vanguard Nigeria, ThisDay Nigeria, Punch Nigeria, Premium Times, Sun News, The Guardian, The New York Times, Sotheby’s, Box Office Mojo, Smithsonian, Forbes.